Return

Return

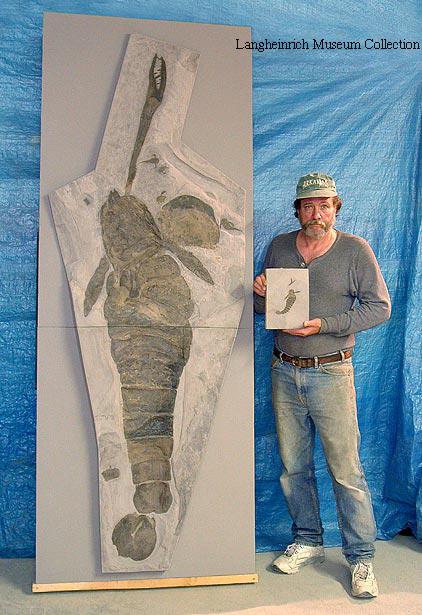

Pterygotus

Pterygotus is the second-largest known eurypterid, or sea scorpion and one of the largest arthropods of all time. It could reach a length of 2.3 m (about 7 feet), had a pair of tremendous compound eyes, as well as another pair of smaller eyes in the center of its head, and 4 pairs of walking legs, a fifth pair modified into swimming paddles, as well as a pair of large chelae (pincers) for the subduing of prey. The foremost 6 tergites, or tail sections, contained gills and the reproductive organs of the animal.

The larger pair of Pterygotus' eyes strongly suggests that it was a visually oriented predator. It used its paddles to swim, though, it could probably accelerate by using its tail as a third paddle. The beast is popularly reconstructed by artists in the act of violently capturing primitive fish.

Pterygotus first arose during the Silurian period, and eventually died out during the early to mid Devonian. It was related to the larger Jaekelopterus and the freshwater Slimonia. Fossils have been found in all continents except for Antarctica. It was one of the top predators in the Paleozoic seas. It lived in shallow coastal areas, hunting fish, trilobites, and other animals using stealth. It would have ambushed its prey by burying itself in sand. Then, when a fish or other unwitting animals came within range, Pterygotus would rise up and grab it with its claws.

Unlike smaller sea scorpions (like Megalograptus for example), Pterygotus could not leave the sea for land to molt or breed. It could, however, live in fresh water as well, probably migrating to lakes and rivers from the seas in pursuit of fish.

Pterygotus was an accomplished swimmer and could move with speed and agility through the water. It would swim by flapping its long, flat tail up and down; the broad, flat part at the end would push it through the water in much the same way as the fluke on the whale's tail does. It would steer and stabilize itself using its legs.

Fossils of Pterygotus are relatively common, although complete skeletons are rare. It was one of the last of the gigantic sea scorpions: later species were much smaller and more nimble. The decline of the larger sea scorpions may be related to their relative slowness and vulnerability to attack by large predatory fish such as Dunkleosteus[citation needed].

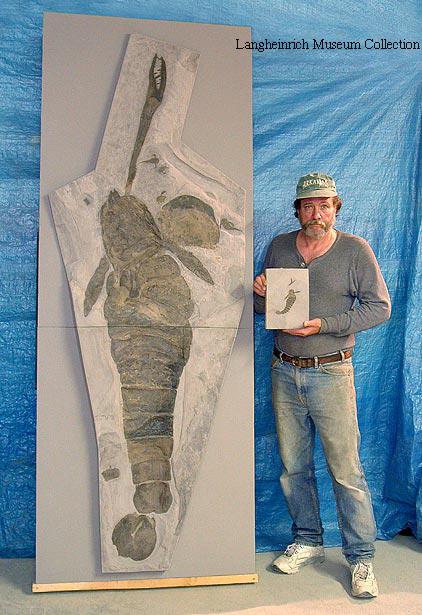

Pterygotus is the second-largest known eurypterid, or sea scorpion and one of the largest arthropods of all time. It could reach a length of 2.3 m (about 7 feet), had a pair of tremendous compound eyes, as well as another pair of smaller eyes in the center of its head, and 4 pairs of walking legs, a fifth pair modified into swimming paddles, as well as a pair of large chelae (pincers) for the subduing of prey. The foremost 6 tergites, or tail sections, contained gills and the reproductive organs of the animal.

The larger pair of Pterygotus' eyes strongly suggests that it was a visually oriented predator. It used its paddles to swim, though, it could probably accelerate by using its tail as a third paddle. The beast is popularly reconstructed by artists in the act of violently capturing primitive fish.

Pterygotus first arose during the Silurian period, and eventually died out during the early to mid Devonian. It was related to the larger Jaekelopterus and the freshwater Slimonia. Fossils have been found in all continents except for Antarctica. It was one of the top predators in the Paleozoic seas. It lived in shallow coastal areas, hunting fish, trilobites, and other animals using stealth. It would have ambushed its prey by burying itself in sand. Then, when a fish or other unwitting animals came within range, Pterygotus would rise up and grab it with its claws.

Unlike smaller sea scorpions (like Megalograptus for example), Pterygotus could not leave the sea for land to molt or breed. It could, however, live in fresh water as well, probably migrating to lakes and rivers from the seas in pursuit of fish.

Pterygotus was an accomplished swimmer and could move with speed and agility through the water. It would swim by flapping its long, flat tail up and down; the broad, flat part at the end would push it through the water in much the same way as the fluke on the whale's tail does. It would steer and stabilize itself using its legs.

Fossils of Pterygotus are relatively common, although complete skeletons are rare. It was one of the last of the gigantic sea scorpions: later species were much smaller and more nimble. The decline of the larger sea scorpions may be related to their relative slowness and vulnerability to attack by large predatory fish such as Dunkleosteus[citation needed].

.

Return

Return